The manager of one of our recommended funds recently described the run up in shares over the past five years as ‘the most unpopular bull market in 50 years’.

There certainly seems to be a great deal of scepticism about the justification for rising share prices at present. In this note we wrestle with the bears by exploring their concerns about the global economy, testing the reasoning of those who believe share prices are over-valued and revisiting the justification for our continued cautious optimism.

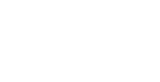

As the chart above shows, equity investors have enjoyed strong rises in share prices over the last five years. Considering that, amidst the turmoil and panic of the crisis, equity prices collapsed by almost 45%, arguably we should not be surprised that markets have recovered strongly since. However, august bodies such as the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) as well as an array of economists and investors do not agree.

According to a recent report from the BIS, ‘euphoric’ financial markets have become detached from the reality of a lingering post crisis malaise. The report went on to recommend that governments abandon policies that risk stoking unsustainable asset price booms and halt the steady rise in debt burdens around the world. Such statements should prompt every investor with equity allocations to stop and re-examine their views.

Global Economy and Risk Assets – The Bearish Case

Consumers and governments remain deeply indebted. As a result, economies are struggling to grow. The global economy is on a life support machine powered by central banks’ zero interest rate policies and fed by quantitative easing – injections of liquidity that have seen the balance sheets of central banks expand hugely. Such wholesale ‘printing’ of new money must inevitably lead to inflation, forcing up interest rates. Higher interest rates will make the servicing costs of debts unmanageable. Defaults will follow and the financial crisis, deferred but not cured by policy measures, will resume.

The investment advice implicit within this analysis is, ‘it’s a trap!’ – risk assets are, along with economies themselves, artificially supported by policy – so stay in defensive assets such as cash, government bonds, and gold. While such views appear to be quite widely held, they have, for the last five years, been wrong – on both the macroeconomics and investment markets.

We need to ask why this bearish view of the world has proven wide of the mark and, perhaps more importantly for those investors who have profited from holding equities, whether it will continue to be so? If we cannot set out a positive case for the global economy and equity markets it might be that we have been lucky – and that the present, quiet period of gently rising markets will prove to be the lull before renewed storm.

We begin answering the bear case by considering an updated version of a table we included in our July 2012 note,

Driven by Value1. Although the data is still only to the end of 2012, the same trends that were apparent two years ago remain in place; household debt as a percentage of disposable income is declining in the US, UK, Germany and Japan. In the eurozone as a whole it is rising marginally, reflecting the stresses in those economies on the periphery of the currency-bloc struggling with high unemployment and structural reform.

Household gross debt to disposable income ratio (%)

(Source OECD Economic Outlook May 2013)

| 2012 | 2010 | Pre-Crisis Level 2007 | Pre-Boom Level 2007 | |

| US | 108 | 117 | 131 | 96 |

| UK | 146 | 158 | 174 | 112 |

| Euro area | 108 | 108 | 104 | 82 |

| Germany | 87 | 90 | 96 | 68 |

| France | 100 | 99 | 89 | 68 |

| Japan | 124 | 126 | 127 | 134 |

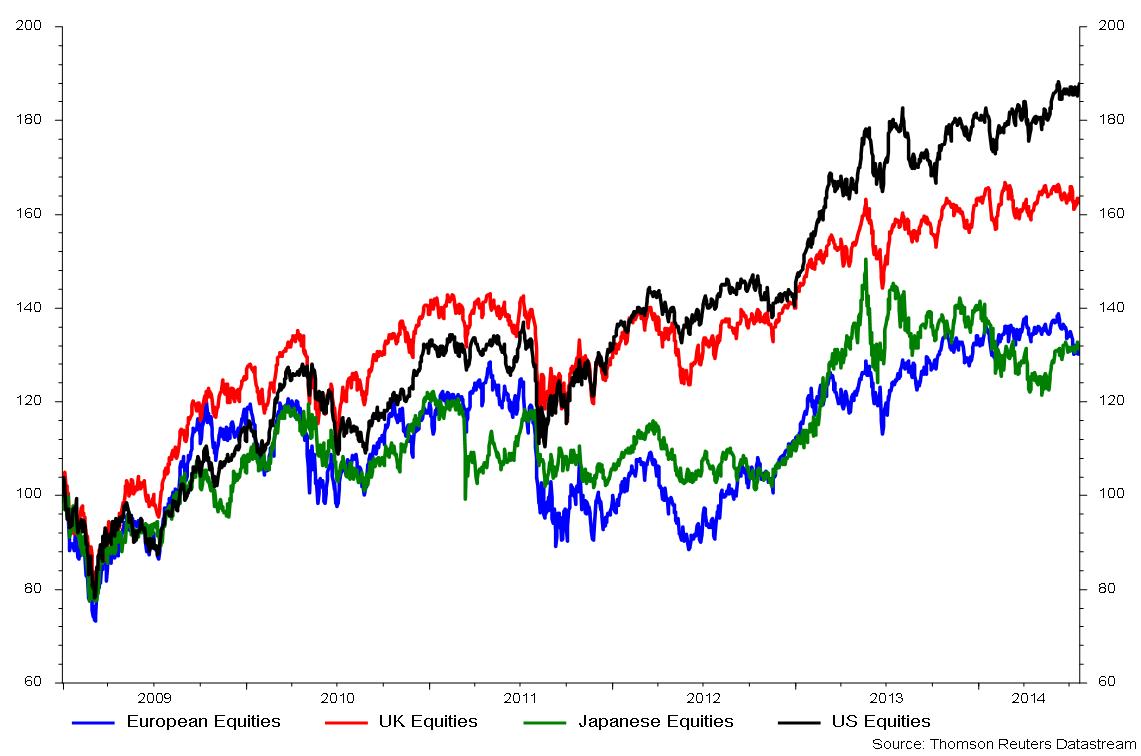

Turning to debt more widely, the following chart shows, for the UK, the progress of debt reduction across the financial and industrial sectors of the corporate world, together with the public sector, and for completeness, the household sector.

Debt as a multiple of GDP is declining, albeit slowly

Debt within the financial sector, hugely bloated by the time of the crisis, is now shrinking rapidly. The non-financial corporate sector was, in general, never overly indebted and debt here is broadly steady. As discussed above, households are slowly repairing their balance sheets. This leaves the government sector, the top layer in the chart above, where debt has expanded since the crisis. The key consideration here is that, faced with banking failures and a sharp recession, governments had little choice but to allow their finances to move into deficit.

As tax revenue and transfer payments, such as unemployment benefits, are extremely sensitive to the level of economic activity, government finances always deteriorate sharply in recessions. To avoid this, the only course of action a government can take is to cut spending to balance the books. This policy, of course, just exacerbates the downturn and risks turning recession to depression. However, with a recovering economy, government finances improve rapidly, as we have seen in the US where the Congressional Budget Office projects that the US public sector deficit will be 2.8% of GDP this year, down from a peak of 9.8% in 2009.

The problem of excessive debt is therefore being addressed, albeit gradually. It is not the intractable issue that will lead us back into financial crisis. The problem is healing.

Turning to the threat of inflation, we can deal quickly with this concern, as it was the subject of our last note to clients, The Dog that Didn’t Bark. To summarise, in our view, inflation has not reared its head in recent times because of the huge deflationary forces weighing on the global economy. These forces include the heavy debt burdens as discussed above, but also include globalisation and technology. To believe that inflation will force interest rates higher against such a backdrop is, in our view, to believe that the laws of economics have been suspended. Put simply, economies are too weak to support higher inflation or withstand higher interest rates.

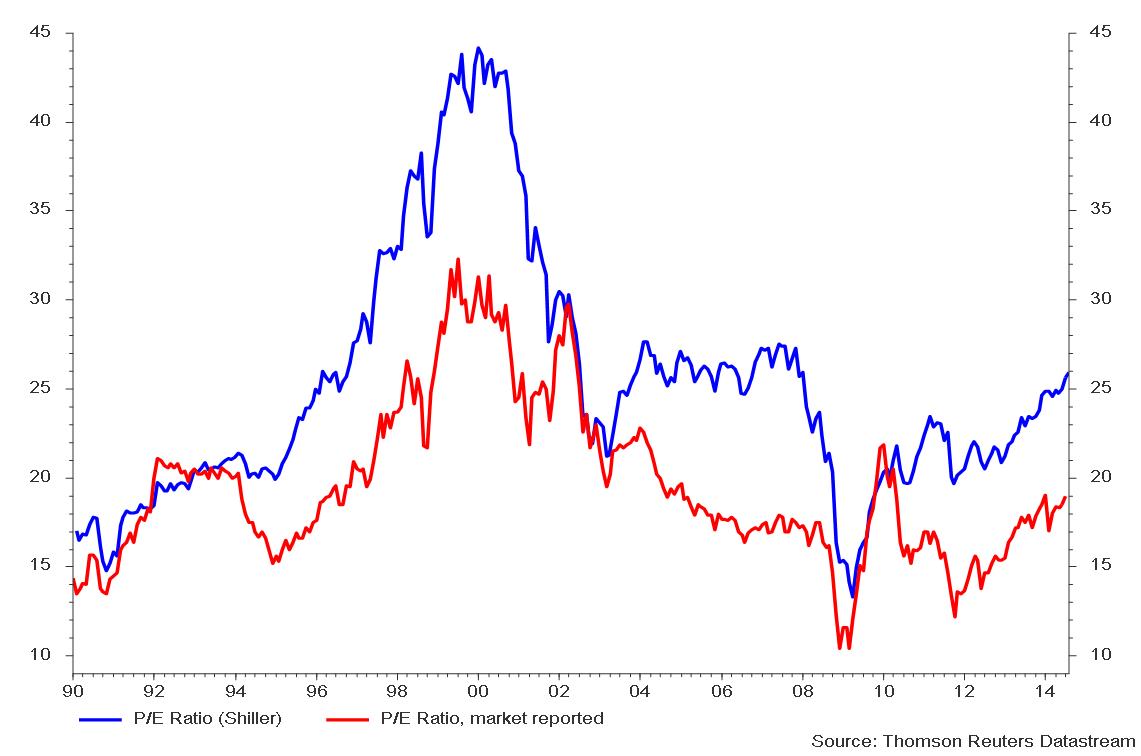

These points address the bear case as set out above. What about inflated equity market valuations? We would argue that, on first inspection at least, equities look broadly fair value. However, the bear case rests on the view that companies are, at present, highly profitable – that is, margins are at record highs. If these were to fall to normal levels, shares would look expensive. This can be seen in the chart below. We have used the US market as it is here that valuations are highest at present. The cyclically adjusted, or Shiller, P/E ratio is calculated by averaging profits over ten years to smooth out the rises and falls in company earnings. Compared to the unadjusted ratio, US shares on this basis do indeed look expensive. However, before concluding that this is a sell signal we should take the following points into consideration.

In our view, the deflationary pressures still present in the global economy, as discussed above, are in two key ways working in the favour of companies.

Firstly, they are weighing down on wage pressures and input costs such as commodities and raw materials – boosting profits for many companies. Secondly, they are keeping interest rates at super-low levels. This helps the corporate sector, as most companies finance their activities with an element of debt. To this, we might add other factors, including the trend towards outsourcing and the greater use of technology as developments that have helped some (but by no means all) companies boost their margins.

Are we arguing that company profits can claim a permanently larger share of economic output? No. That would certainly be rash, but there are reasons to believe that margins are not going to decline rapidly in the near term. If margins can be maintained and corporate profits can grow as economies continue to expand, there is every reason to believe that equity markets can make further progress.

In this note, we have argued that there are grounds for continued optimism. This is based on the belief that governments and central banks will continue to choose policies to support growth and allow the global economy time to heal. This reasoning has been broadly unchanged for the past two years and it has provided the rationale for our higher equity allocations over that time. We remain cautiously optimistic.

In the interest of improving our communications, any feedback, comments or questions you have would be most welcome. Please direct feedback either to my email below or to our Marketing and Business Development Director, Beverly Landais, at beverly.landais@saundersonhouse.co.uk or 020 7315 6500.

Click here to download a pdf of the article

Christopher Sexton

Investment Director

D: 020 7315 6506 E: chris.sexton@saundersonhouse.co.uk